Rachel Barrowman's much anticipated biography of Maurice Gee is released this Thursday (9 July) and ahead of the release we asked her about her experiences working on the book.

How long has the bio

taken you? When did you begin?

I started working on it midway through 2006. It’s

taken me quite a lot longer than I anticipated – which is all to do with life –

mine – getting in the way along the way. Also, Gee has had a long and very productive writing

career – seventeeen adult novels, thirteen children’s novels, a volume of short

stories (and writing for screen). So it was always going to be a big job.

When did you first

approach Maurice Gee about the bio? Had he had other offers?

It wasn’t quite exactly a

matter of me approaching him. One or two people had been gently persuading him

that there should be a biography, and that it would be better that it was by

someone he was comfortable with and had said yes to, that he should take the initiative; if he kept refusing, someone would go ahead and do one anyway. At the same time, I needed a project and I was suggested to him. He

had read my Mason biography and liked it. I think I was unthreatening as a

potential biographer.

So one day in 2006 he contacted me and asked if I

would be interested in recording some interviews with him. He’d decided he

needed to, that it was time to get some stuff down on record – and that if I

wanted to go on from there and do a biography, he was (albeit still hesitantly,

I suspect) happy with that. He would regard me as his ‘authorised’ biographer

to the extent of turning anyone else away. So we went ahead with the interviews

and I applied for and got the Michael King Fellowship.

What was he like to work

with?

He was very open, generous and honest. He said at the

outset that he didn’t like the term ‘authorised biography’, in the sense that

it implied he was maintaining/wanted to exert control. It was to be my book, he

wouldn’t interfere. As far as he was concerned there was no point in doing a

biography if it wasn’t to be ‘warts and all’, and he said that he would be as

honest and open with me as he could.

So he didn’t place any constraints around it (except regarding

a couple of subjects where other members of his family were involved and where he

told me he would need to know they were happy with them being written about –

so that was about their sensitivity, not his. But in the end there were no

issues there). There were, it’s true, one or two things he was

reticent about in those initial conversations and which I came across in my

research, but he was forthcoming when asked.

Five or six months after I got started he and

Margareta moved from Wellington to Nelson, and since then our communication has

mostly been by email: me asking questions as I went along, him remembering or

elaborating on things, and also keeping me up with what he was doing. He was

still writing – four novels published since 2006.

What were some surprising

details you discovered about his life?

I really didn’t know anything much about Gee’s life,

so there was all sorts of stuff that was new and fascinating. Dedicated readers

of Gee’s work will know that his fiction draws heavily on his childhood and

family history, and the few (short) pieces of memoir he’s published have

covered that territory, but there’s a lot else that he has not previously

spoken or written (directly) about publicly.

You’ll have to wait for the book to find out more

though!

One thing I didn’t know was that he’d written quite a

bit for television: Mortimer’s Patch,

notably (early 80s small-town cop show, very successful), and a feature film

(starring Patrick McGoohan of The Prisoner

fame).

The bio is also very much

about his fiction – did you reread all the books? Did you get the sense of themes he would return to/characters

he would reinvent in the novels?

When I first started working on the biography, the

first thing I did – alongside the interviews – was to read them all in order of

publication. I hadn’t read all the novels: not the

pre-Plumb ones, with the exception of

In My Father’s Den which I only read

after the film came out, and I’d read few of the short stories. Nor had I read many

of the children’s novels – only The Fat

Man and Hostel Girl, and none of

the fantasy ones. Now I’ve read them all at least twice and many of them three

times.

Repetition, echoing – of themes, incidents, places,

images and metaphor – is a significant feature of Gee’s work. A fugue-like

quality. (This is also a quality of the novels themselves: Plumb, and the Plumb

trilogy, especially.) Reading the novels (and the short stories) through in

order, what comes through very strongly is not just the sense of Gee’s distinctive

‘territory', but the novels’ own life story, if you like, how they relate to,

speak to one another, either distantly, and through the commonality of language

and metaphor, etc, but sometimes more directly, as in The Fire-raiser providing the basis for Prowlers, and Hostel Girl

for Ellie and the Shadow Man. Often

those connections are smaller and less conscious, and it was fascinating to

recognise them. I enjoyed reading and re-reading the novels (and

stories) very much and I’ve written more about them than I think I anticipated

I would when I started.

Did you have any favourites?

When pressed for a favourite I might say Prowlers, which is Gee’s favourite too. It was the first novel he wrote after the Plumb

trilogy and the enjoyment he had with it is palpable. And I have a special

fondness for A Special Flower, which

is probably his least known novel (it’s the second), and the least Gee-ish

(though in some ways it’s very Gee). A quite strange, creepy novel. It’s also

the one novel he has not wanted to see reissued.

Of the children’s novels: The Fire-raiser, The Fat Man

and Hostel Girl. I’m less a fan of

the fantasy novels but that largely reflects my own reading preferences.

How was the process of

researching and writing different or similar from the Mason bio?

Quite different in a number of respects. Firstly,

Mason died in 1971, so I couldn’t go straight to the source, so to speak, as I

could with Gee; nor to contemporaries.

I started the Mason bio with a

previous, unpublished biography and the research for that biography available

to me as a starting point – though the book quickly became my own and I

supplemented that material with my own research. But you could say I had a

‘head start’. With Gee it was all mine from the outset.

Thirdly, Mason’s literary oeuvre was quite small. Gee

has had a 50-plus-year writing career, which has produced 33 books. So it was

bigger deal, in a number of ways. Certainly it felt like a bigger challenge

(and for all those reasons).

But in terms of my own method, and my approach in

terms of style and form, these were pretty much the same. With the form and style

of the biography – a chronological life narrative, weaving the story of the

literature in with that of the life, wanting to let Gee’s character and the

themes emerge from the narrative and quotation and not be too heavy-handed or

directorial – I was aiming for the same thing.

How does it feel to

complete the book?

A little unreal; a little scary.

What do you think

literary biographies add to a body of fiction or non-fiction work?

I find it hard to answer this. The relationship

between the literature and the life is really the point of ‘literary biography’.

Of course. But of course, the extent to which and the ways in which they relate

will vary hugely from subject to subject. With Maurice, those connections are

pervasive and subtle and, I believe, important.

This is not to say that one needs to know about the

life to appreciate the novels; not at all. But the two do inform each other, in

subtle and not so subtle ways.

Are you nervous about

Maurice's reaction to the book?

No, because he has already read it. I sent it to him

when (and only when) I had a complete draft done, which was in August last

year. Naturally I was nervous. But his response has been very generous.

How he will feel once it’s out there in the world is

another question, of course. (I think we’ll both be feeling a little

terrified.)

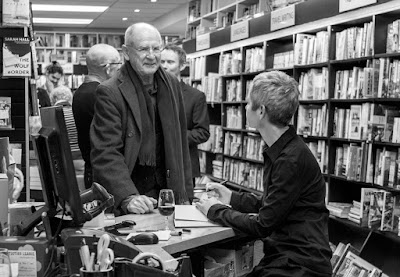

Maurice Gee: Life and Work is released on Thursday 9 July. A launch for the book will be held at Unity Books in Wellington. All welcome.