Damien Wilkins gave a wonderful speech to launch the book, and Fergus Barrowman closed with a telegram from Mr Gee in Nelson. Thanks to Damien and Maurice for allowing us to publish their kind words here.

|

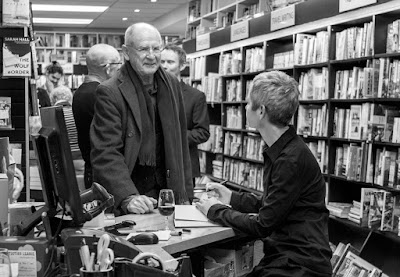

| Damien Wilkins, Fergus Barrowman and Rachel Barrowman (photo credit: Jane Harris) |

It’s a real honour to launch this book. We’ve all been waiting for

it, looking forward to it, hassling Rachel about it, bugging her for Gee

gossip—what secrets did the great man tell her? What has she discovered through

her elegant and subtle and persistent sleuthing? So finally to have it in our

hands—and to weigh such a handsome hardback, feel its solidity and significance—I

imagine it not only as a terrific release and relief for Rachel but seriously

as a special and moving moment in our culture, and a gift to us.

I say it’s moving because Maurice Gee writes fiction. That’s what

he’s done with his life. And then for someone to come along, someone who was

born the year after Gee published his first novel, someone skilled as a cultural

historian but also beautifully responsive as a literary reader, and devote

almost ten years of her life to researching and thinking about and writing the

story of that fiction writer’s life—I find that powerful and affecting. 500-page

biographies of New Zealand writers belong to a rare species. And I can think of

no better photo opportunity for the Minister of Arts and Conservation, Maggie

Barry, than to be pictured cuddling this book before it’s released into the

wild. The Minister isn’t here so let me do a bit of cuddling.

There’s a great photo in this book of Maurice Gee in a white

singlet digging a hole for his septic tank. You don’t have to think for too

long before coming up with its symbolic appeal. Yes, this writer has been excavating

our waste systems for decades. What’s especially good about the photo is that

it captures the process at its dirtiest. I mean Maurice looks buggered,

straddling the hole, the sun beating down on his red face and neck, piles of

fresh dirt around, broken bits of concrete. It’s been awful out there on the

slope beneath the house but you’re going to feel good once it’s done and you

know you haven’t paid another man to do it for you.

It’s an image then we can savour not only for its tempting literary

meaningfulness but also for its suggestion of graft, labour, commitment and

self-reliance. We use the phrase ‘a work of art’ fairly loosely and

unthinkingly, hurrying to the created thing. One of the contributions high

quality literary biography can make is to remind us of how an art form such as

the novel is work—a matter of showing up each morning, putting in the hours,

being dissatisfied, getting it right—as right as it’ll come—and signing off on

it before moving on to the next job. You might even get paid. Luckily for his

readers, though not always easily for Maurice Gee, the job of novelist seems to

have been the only thing he was good at. Although I’m sure he did a fine job

with the septic tank.

Of course everyone is interested in money and writers are

interested in what other writers earn. So the question is: How do you go about constructing

your income stream if all you really want to do is make up stories? Read in one

way this book is a sort of instruction manual for anyone with an interest in

following suit or simply following how one writer did it. And I value intensely

Rachel’s dedication to such details. She’s down in that hole with Gee, getting

dirt on her shoes and working up a sweat. But of course the story is much more

than royalty statements, grant applications, the odd windfall, the many

setbacks . . .

For a start there are all those books to read and consider in the

light of the life being revealed. This biography is thoroughly engaged with Gee’s

fiction and Rachel’s expert delineation of the family tree, the family Gee, which

sets out how one book is connected to another, this is tremendously valuable. And

it’s never done in the niggardly way which aims to shrink everything to a neat

template of correspondences—here’s the real creek and here’s the invented one. When

Rachel tests the life against the work she wants to amplify and enrich and

suggest. And I especially like one aspect of Rachel’s account of the writing—that

is, she always leaves in place the author’s own avowals of ignorance (‘I don’t really

know what I’m doing’), of uncertainty (‘I tried to get close to that experience

but who knows’), of fear (‘I seem to have come to an end’). These are recurring

notes. Partly, of course, they’re a form of self-defence. The aw gee-shucks of Gee. But Rachel

understands too that these moments communicate something about writing itself;

that it always takes in the possibility of not writing, of not turning up for

work. Gee may present as an unpretentious carpenter—look at the cover shot,

sleeves rolled as if thinking how to tackle the skirting board—but his life

story is remarkably chancy and non-compliant, made from unlikely leaps as much

as from dogged toil. From the outside we discern steady progress, books written

as regularly as eggs laid, but finally we see inside the life and understand something

of its costs, its crises, its victories too. A small example: It’s amazing to

me that Gee struggled so much with Meg,

a novel I think of as kind of perfect. It’s amazing that Prowlers was originally called Papps.

Let me finish by saying one more thing about the scope of this

book. Anyone’s life becomes on closer inspection a group portrait and although

Maurice Gee’s career must do without creative writing courses, Rachel convincingly

recreates the friendships and relationships that in many ways mimic the kind of

support structure available now. There’s a lovely evolving set of insights into

how people such as Maurice Shadbolt, Kevin Ireland, Robin Dudding, Ray Grover,

Nigel Cook and others interacted with our man. Gee’s friends are Rachel’s

friends too and therefore ours, helping us see her subject from different

angles. When Gee was doing scriptwriting for television and earning better

money, Shadbolt reports back to Ireland that at the Gee house there are ‘hints

of prosperity’—‘hard booze in the cupboard now instead of home brew.’

I think Rachel’s feel

for the telling remark, the revelatory incident, from what must have been a

large archive of letters, interviews, essays, reviews, as well as the fiction

itself, lends her text not only its narrative drive but also its tone. The book

sounds like Maurice Gee without being his mouthpiece. It’s intimate but also

pitched at a crucial remove. This poise allows the book to be fundamentally

sympathetic to its subject without sacrificing loyalty to facts which emerge

that the hagiographer or even simply the fan might baulk at. I mentioned at the

start this business of secrets, new things about Gee’s life that will alter how

he’s read. I’m sorry but I’m not telling. Rachel’s biography needs to be

purchased to learn these things.

Obviously you’ll want to read it to know how

the Plumb trilogy came to be written. Or Prowlers.

Or Going West. That would be enough. But

such is Rachel’s achievement that gradually you feel something else going on. Through

scrupulously attending to this remarkable individual, the biography’s single

focus starts to do that wonderful thing: it expands, it blossoms, and somehow captures

the broad view of a society in motion; it lets us see not just how he lived but

how we lived too. That also feels fully in tune with the working art of Maurice

Gee.

–Damien Wilkins, 9 July 2015.

A note from Maurice Gee

Reading Rachel's book has been a

strange experience for me. Seeing my life unroll again, or play as though on a

screen, made me want to applaud myself for getting so much done, in work and

relationships, and at other times had me squirming with embarrassment at my

stupidities and shrinking with shame at cruelties and waste.

It's all in the book. This is the

biography I asked for when Rachel and I first spoke about it nine years ago.

'Put in whatever you can find,' I said, not quite understanding that she'd find

so much. But I don't like biographies with holes in them. This one has no holes

except for those Rachel has uncovered in her research and looked into with a

clear eye. The research has been thorough, unrelenting, illuminating -

illuminating even for me.

Did I really do those things? Yes, I did. And I had

those two larger than life grandfathers, that saintly grandmother, that

generous tough-guy father, that happy then sad, beautiful and gifted mother. I

lived that energetic childhood and misshappen adolescence and young manhood,

before coming to what I call my second life, with Margareta, my wonderful wife,

with our daughters and my son - the writing life that they made possible.

Rachel has knitted the parts

together with skill and patience. She has shown where the novels came from,

surprising me with her insights. She has written it clearly and with style. I'm

biased of course but I think this is a biography full of life, and a

wonderfully readable book.

Thank you for it, Rachel, and thank

you for giving me so much of your own writing life.

–Maurice Gee, July 2015

Maurice Gee: Life and Work is on sale at all good bookstores now.

You can also purchase it at VUP's online bookstore here.

$60, h/b.

No comments:

Post a Comment